To a great extent, mystery is desired by man. It is not that he cannot understand, or enter into, or grasp mystery, but that he does not desire to do so. The sacred is what man decides unconsciously to respect. The taboo becomes compelling from a social standpoint, but there is always a factor of adoration and respect which does not derive from compulsion and fear.

(Ellul 142)

Jacques Ellul wrote the above passage in France during the 1950’s, in a dense volume that would eventually be translated and republished in the U.S. as The Technological Society. This belief in the sacred as an important feature of human life serves as the the keystone for his broad analysis and criticism of technological culture. For Ellul, the presence or absence of the sacred within a society influences the extent to which that society places emphasis on pure scientific knowledge versus applied science, or technique:

Technique worships nothing, respects nothing. It has a single role: to strip off externals, to bring everything to light, and by rational use to transform everything into means. More than science, which limits itself to explaining the how, technique desacralizes because it demonstrates… that mystery does not exist. Science brings to the light of day everything man had believed sacred. Technique takes possession of it and enslaves it… Everything which is not yet technique becomes so. It is driven onward by itself, by its character of self-augmentation.

(Ellul 142)

This sounds like a more direct (and pessimistic) version of the idea commonly attributed to Marshall McLuhan that “we shape our tools and then our tools shape us.”

The image of a self-augmenting technological apparatus engaged in ecophagy forms the fictional backdrop of Accelerando by Charles Stross, written a half century after Ellul’s book. In the novel, clever (but not wise) humans create a breed of autonomous marketing scam-bots that multiply inside the information economy. The bots outlive their creators, and once the gap between computing networks and the physical world is bridged, they become a powerful hive mind capable of manipulating physical reality at scale. Their raison d’être is to convert the entire substance of the earth into energy, to facilitate the expansion of the hive further out into the universe. Seeking to transform everything into means in a manner closely resembling the Paperclip Maximizer hypothesis.

Ellul’s answer to the question of whether or not tech has a moral character hinges on the act of creative application. The understanding of a thing is essentially neutral, but the act of projecting that knowledge onto reality has moral implications more complex than the individual technician can comprehend.

Contrary to the claims of his 20th century critics, Ellul was not advocating for technophobia or the return to an imaginary golden age. The cautionary punchline of Technological Society is to beware the consequences of discarding humanism in exchange for a religious devotion to science and materialism.

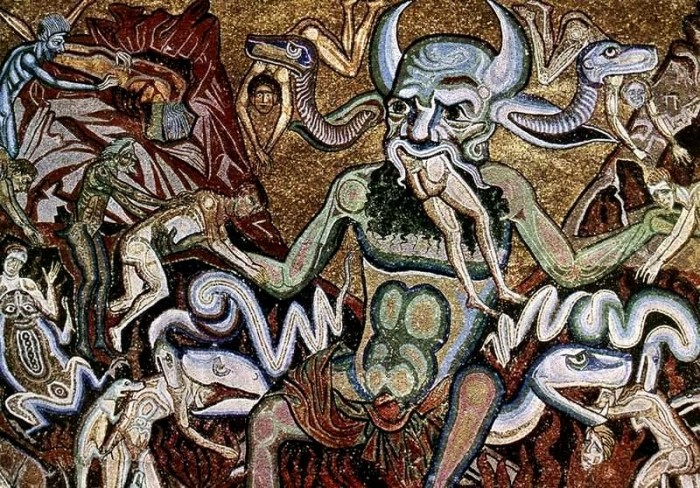

From this perspective, the traditions of esotericism in previous cultures may have been a self-preservation tactic. If tech alters reality and influences human behavior to serve its own rational self-augmentation above all else, then the impulse to restrict or avoid certain information may not always be motivated by baseless fear or a desire for power, but rather a healthy respect for the potential destructive outcomes of letting genies out of bottles.

References:

Ellul, Jacques, et al. The Technological Society. Vintage Books, 1964.

Stross, Charles. Accelerando. Ace, 2006