On the contrast between Renaissance and Reformation attitudes about nature and sin, after reading Ioan P. Couliano’s Eros and Magic in The Renaissance:

The idea of liberty, which allowed man to belong to the higher beings, ends by becoming a crushing burden, for there are no longer any points of reference… To read the “book of Nature” had been the fundamental experience in the Renaissance. The Reformation was tireless in seeking ways to close that book. Why? Because the Reformation thought of nature not as a factor for rapprochement but as the main thing responsible for the alienation of God from mankind. By dint of searching, the Reformation at last found the great culprit guilty of all the evils of individual and social existence: sinning Nature.

(Couliano 208)

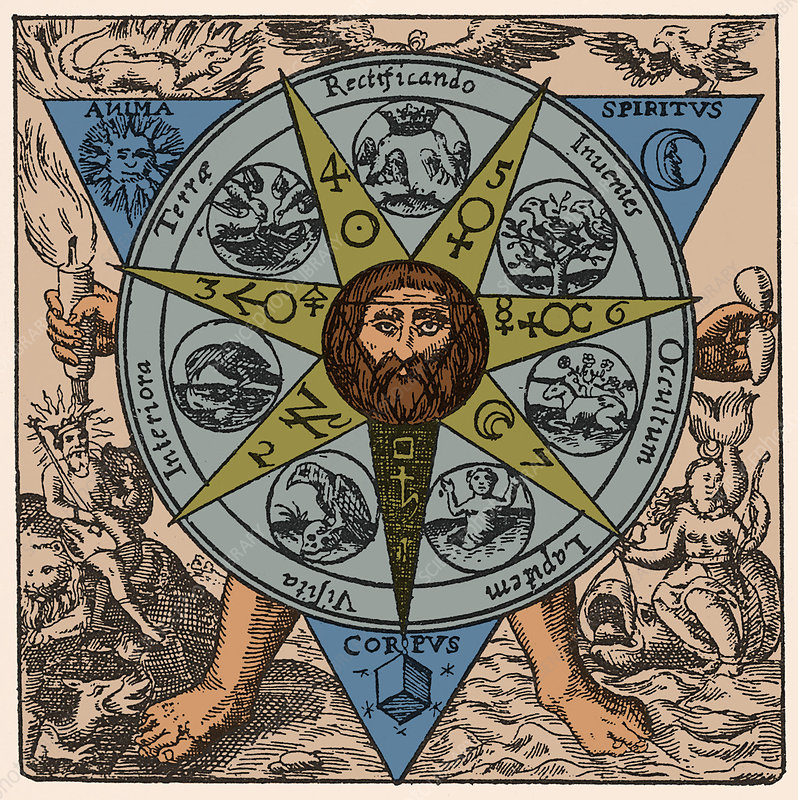

Couliano bases his claims on historical examples from the upheaval of 15th-17th century European culture. Prior to the theological and political schism of the 16th century, the Roman Catholic church of the Renaissance was relatively liberal. Ancient classical literature, Asian and near-Eastern philosophical and scientific texts, and even contemporary occult writings where preserved in the libraries of the church throughout the late Medieval and Renaissance era. Many occult scholars and mystics of the 1400-1500’s were also members of the clergy. Johannes Trithemius (1462-1516) was a notable example of this ambiguity. Trithemius was a Benedictine abbot. He was also an influential occultist and cryptographer.

The meaningful phase transition in western culture, according to Couliano, was not about the conflict over theological details between the protestant and papal factions, but an all-consuming radical authoritarianism that influenced both catholic and protestant society. The bifurcation of culture was one of style, not substance: all western thought gravitated towards a negative view of nature and rejection of a divine and infinite cosmos like the one expounded by such thinkers as Giordano Bruno.

Once physical reality was deemed inherently sinful and disassociated from the divine, scientific knowledge was no longer constrained by the sacred. The focus of human activity became the control and domination of nature through the application of science. This worldview eventually reached mature expression in the 17th century materialism of Thomas Hobbes and his famous observation from Leviathan:

In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

(Hobbes 84)

For Hobbes, writing in 1615, it was a presupposition that commoditizing the natural world to advance material prosperity was humanity’s prime directive, and a powerful authoritarian state was the best way to accomplish this. The nuanced view of nature as a complex manifestation of intelligence was going out of style. The new materialist myth of progress provided the cultural foundation for the global technological society, with all the associated wonders, horrors, and diminishing marginal returns that define the present day.

References:

Couliano, Ioan, et al. Eros and Magic in the Renaissance. Amsterdam, Netherlands, Amsterdam University Press, 1987.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan: Or, The Matter, Forme & Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civill. United Kingdom, University Press, 1904.